New Attacks on the Administrative State

Right-Wing Attacks

American right-wing extremists are attacking the administrative state. In a recent interview with David Brooks, Steven Bannon says a second Trump administration must “go to war with the existing administrative state.” Here Bannon cites Project 2025, a multi-pronged initiative to completely overhaul the federal executive branch if Donald Trump is reelected in November. As Paul Krugman urges in a recent column: “Don’t Lose Sight of Project 2025. That’s the Real Trump.”

The massive policy handbook of Project 2025 is titled Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise. In its foreword, Kevin Roberts, President of the Heritage Foundation, states that one of its top four priorities is to “dismantle the administrative state and return self-governance to the American people” (p. 3). (The other three priorities are to “restore the family as the centerpiece of American life,” defend the United States “against global threats,” and “secure our God-given individual rights to live freely.”) Roberts is dead serious about this. It was he who, on the eve of this year’s Independence Day, boldly announced a “second American Revolution” and threatened that it will be bloodless “if the left allows it to be.”

Supreme Court Rulings

Even as right-wing ideologues like Bannon and Roberts attack the administrative state from without, the United States Supreme Court is gutting it from within. As Charlie Savage explains in The New York Times, two of the “sweeping rulings” the conservatively dominated Court issued at the end of June “will hamstring the ability of regulatory agencies to impose rules on powerful business interests.”

U.S. Supreme Court building, Washington, D.C. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith , Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

By overturning the forty-year-old “Chevron doctrine,” the Supreme Court has given judges permission to ignore the expertise of federal agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency when interpreting their regulations. The Court has also made it harder for federal agencies to use their own in-house tribunals to enforce such rules. Instead, they’ll have to sue accused rule-breakers such as industrial polluters in federal courts.

Together these recent rulings undermine the legislative authority and regulatory enforcement power of the administrative state. The Court has relocated these in a judiciary that, by historical precedent and by constitutional design, has neither the expertise nor the mandate to generate and enforce administrative laws.

Constitutional Democracies

Until recently, few citizens in the United States or elsewhere had heard of the “administrative state” or wondered whether it should be dismantled. Nor are many of us familiar with the extensive debates waged by political and legal theorists about the role and legitimacy of administrative law in a constitutional democracy. Yet current political struggles between what “Waking Nightmare” calls “authoritarian populists” and their more liberal or progressive opponents often turn on such issues.

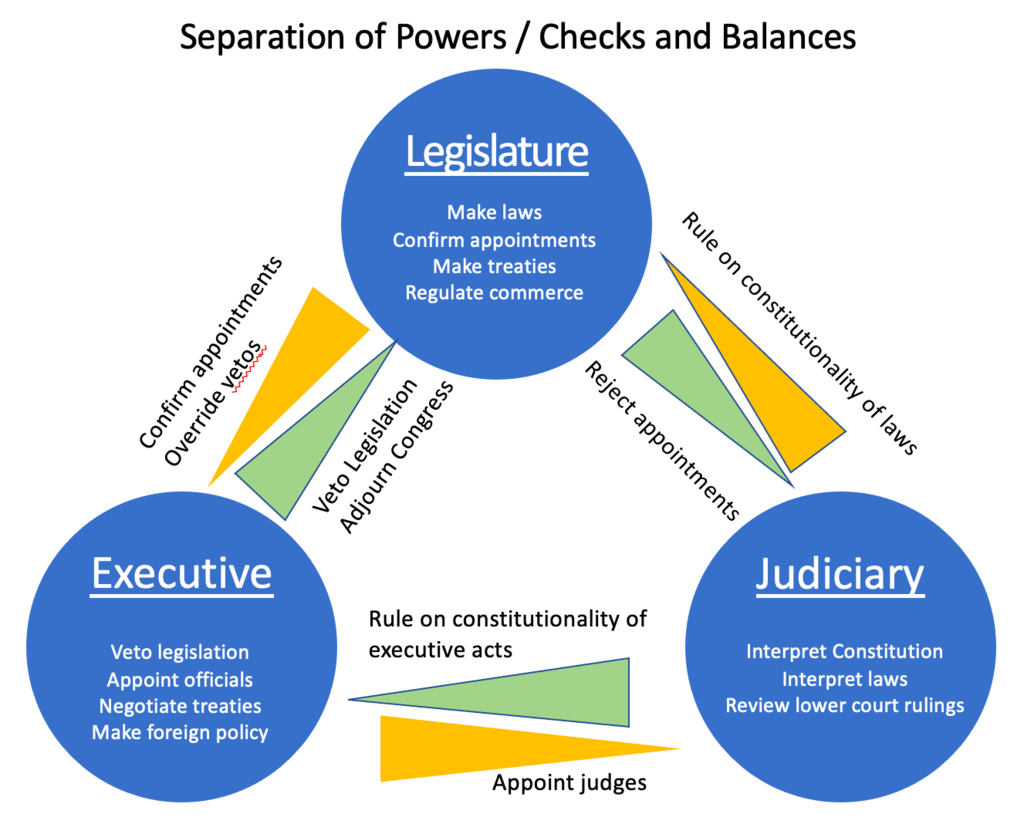

Constitutional democracies rely heavily on two architectural features: the rule of law, and the separation of legislative, executive, and judicial powers. Laws should emerge in the legislature (e.g., the U.S. Congress or Canadian Parliament) via democratic deliberation and negotiation, and, while protecting minority rights, they should reflect what most citizens think public justice requires. This assumes that both citizens and government officials will abide by these laws, at least until they are changed; that the executive branch will enforce them in legitimate ways; and that, in cases of disagreement, an independent judiciary will sort out where, when, and how the laws apply.

Opening lines of the U.S. Constitution. Image by Navyatha123, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

That, at least, is the architectural framework. But constitutional democracies have always been more complicated than this. Moreover, in the late nineteenth century governments began to take on new roles not clearly foreseen or spelled out in founding documents like the U.S. Constitution, new roles that raise questions about the separation of powers and the rule of law.

New Roles

These new roles emerged from social policies that address unemployment, health care, and old age. They also arose from economic policies aimed at national infrastructure (e.g., railways and roads) and at the capitalist economy (e.g., trade, taxation, and financial regulation). As a result, many new bureaucracies were created and became part of what historians call the welfare state.

State administrative center, Brussels. Photo by Ddr, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The number and scope of such bureaucracies exploded after the Second World War, creating what can now be called the administrative state: the complex network of government agencies that have the power to write, enforce, and adjudicate their own laws. Many new areas have required government attention, including nuclear energy, the environment, mass immigration, new technologies, and the internet. Further, government agencies increasingly have had to develop their own regulations and their own ways to enforce and adjudicate them: lawmakers and judges typically lack the expertise to work out the details of what, for example, environmental laws and immigration policies require.

Hence the administrative state has absorbed many legislative and judiciary functions. This makes the executive branch of government ever more powerful and, potentially, unaccountable for its actions. It also raises three sorts of questions.

Three Questions

First, has the consolidation of distinct powers (legislative, executive, and judicial) in the administrative state given governments too much power and made them unresponsive to “the will of the people.” In other words, have constitutional democracies become fundamentally undemocratic?

Separation of Powers in the U.S. government. Created by AboutPolitics, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second, do democratically elected legislatures violate their proper role when they delegate their lawmaking powers to unelected administrative agencies? Do the courts also undermine their proper role when they defer to how an administrative agency interprets the laws in its domain? In other words, has the growth of an administrative state made constitutional democracies fundamentally unconstitutional?

Third, how should popularly elected or legislatively appointed members of the executive branch (in the United States, for example, the president and members of cabinet) relate to the unelected civil servants who staff and run administrative agencies? Should the power to hire and fire personnel reside in the elected executive, thereby making it more likely that political persuasion rather than professional competence sets the tone? Or should this power reside in administrative agencies themselves, thereby increasing the chances that, despite their competence, civil servants operate with unchecked impunity? Indeed, do tensions between a politically elected executive and a professionally qualified civil service (for example, between former President Trump and the federal Department of Justice) make constitutional democracies fundamentally ungovernable?

Destruction or Control?

Donald Trump and Project 2025 take stands on all three questions. They think the administrative state has too much power, that it usurps legislative and judicial prerogatives, and that it needs to come under the president’s control. Philosophically, that’s what lies behind their calls to “dismantle” the administrative state. It also lies behind the Supreme Court’s recent rulings.

Yet authoritarian populists like Trump do not actually want to dismantle the administrative state. Rather, they want to shut down those agencies whose “woke” policies they deplore (e.g., the Department of Homeland Security, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau) while bringing all others into line with their own political agenda. There’s no talk, for example, of dismantling the Pentagon, whose enormous military budget constitutes more than half of the federal government’s discretionary spending.

Their strategies will concentrate even more power in the elected executive. This will create what political thinkers call an “imperial presidency” that neither respects the rule of law nor honors the constitutional separation of powers. Instead it will give carte blanche to captains of commerce who’d rather not pay taxes, protect the environment, or offer their workers a living wage. The implications for environmental policy are downright scary, as a recent article in the New York Times shows.

Photo by Pedro Ribeiro Simões from Lisboa, Portugal, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Despite the legitimate concerns behind authoritarian populists’ attacks on the administrative state, then, their understanding of constitutional democracy is deeply flawed. And their remedies are dangerously anti-democratic. Their attacks challenge us to reimagine how the administrative state can foster solidarity and justice. We need to rediscover the legitimate roles of administrative agencies in a constitutional democracy.

Note: If you wish to receive notices of my blog posts in the future, please email me using the contact link on this website.